This is the story of the radicals who came from, and fought, Scotland’s fossil fuel industry.

Fossil fuels get little mention in official histories, yet they have powered our economy and shaped our society for centuries.

Scotland’s political landscape has been shaped by coal and oil, and the industries that extracted them have been shaped by workers and social movements.

The Labour Movement is Born in Scotland’s Mines

From the 18th century onwards coal mining was one of Scotland’s major industries. Miners faced extreme danger, appalling working conditions and poverty pay.

The Blantyre Mining Disaster of 1877 in Lanarkshire was Scotland’s worst mining disaster.

Listen to traditional song ‘The Blantyre Explosion’, performed by Katherine Campbell:

“When the news was made known

Verse from ‘The Blantyre Explosion’ (*, *)

all the hills rang with mourning

Two hundred and ten Scottish miners were slain.”

Miners organised to improve conditions and provide shared services. The Leadhills Miners Library, Lanarkshire, founded 1741, is the oldest subscription library in Britain. Leadhills was also the site of one of the first recorded strikes, in 1836.

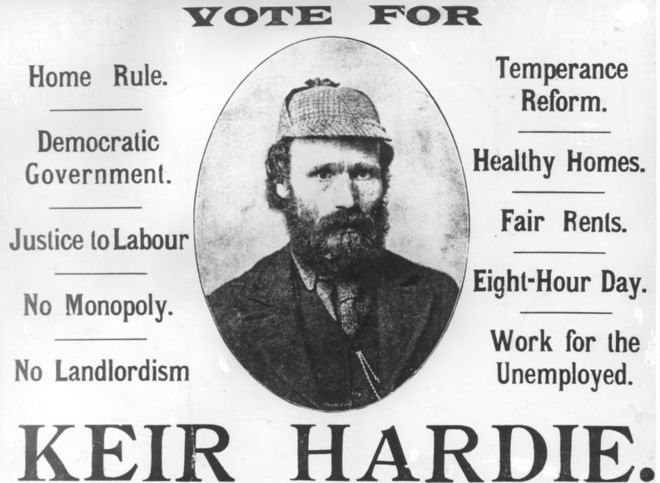

Mine workers created some of the first trade unions and would eventually enter the Houses of Parliament: the Labour party was born.

“More and more the House of Commons tends to become a putrid mass of corruption, a quagmire of sordid madness, a conglomeration of mercenary spiritless hacks dead alike to honour and self-respect.”

Keir Hardie, Scottish mining union organiser enters Parliament in 1892 (*)

From these seeds trade union struggle would go on to win basic rights which are now widely enjoyed:

- Maximum working hours

- Paid holidays

- Forced employers to abide by contracts

- Paid parental leave

- Tackling discrimination

- Minimum Wage

- The weekend (*)

Labour, Tories and ‘Scotland’s Oil’

Oil was discovered in the North Sea in 1969.

Energy Minister Tony Benn sought public control over North Sea oil before the Labour Government fell in 1979.

On 18 June, 1975, the first oil from the North Sea arrived at the Isle of Grain refinery… It was welcomed by the new energy secretary, Tony Benn, nursing a bottle of the stuff, saying: “I hold the future of Britain in my hand.”

The Scotsman

“The North Sea is not a Socialist sea. Its oil is not Socialist oil. It was found by private enterprise, it was drilled by private enterprise, and it is being brought ashore by private enterprise.” (Applause.)

Margaret Thatcher addresses 1977 Conservative Party Conference (*)

“It was oil revenues that bankrolled the unemployment, the destruction of manufacturing, the high-exchange rate, the termination of British coal mining, and the big-bang that turned London into a capital of global neo-liberalism and pumped growth into the South-East in the early 1980s.”

Anthony Barnett (*)

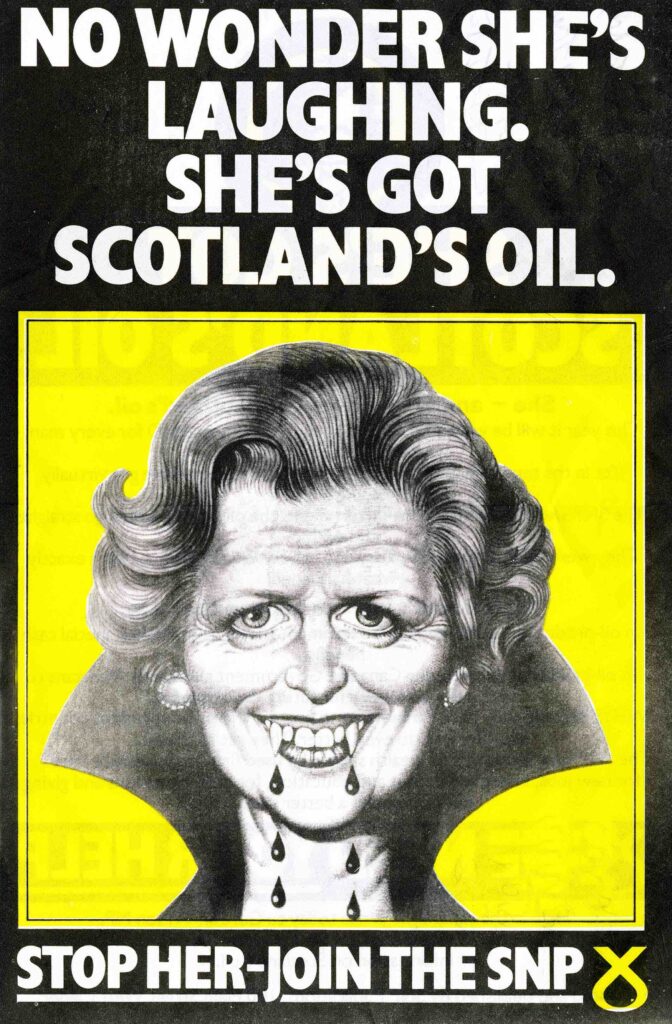

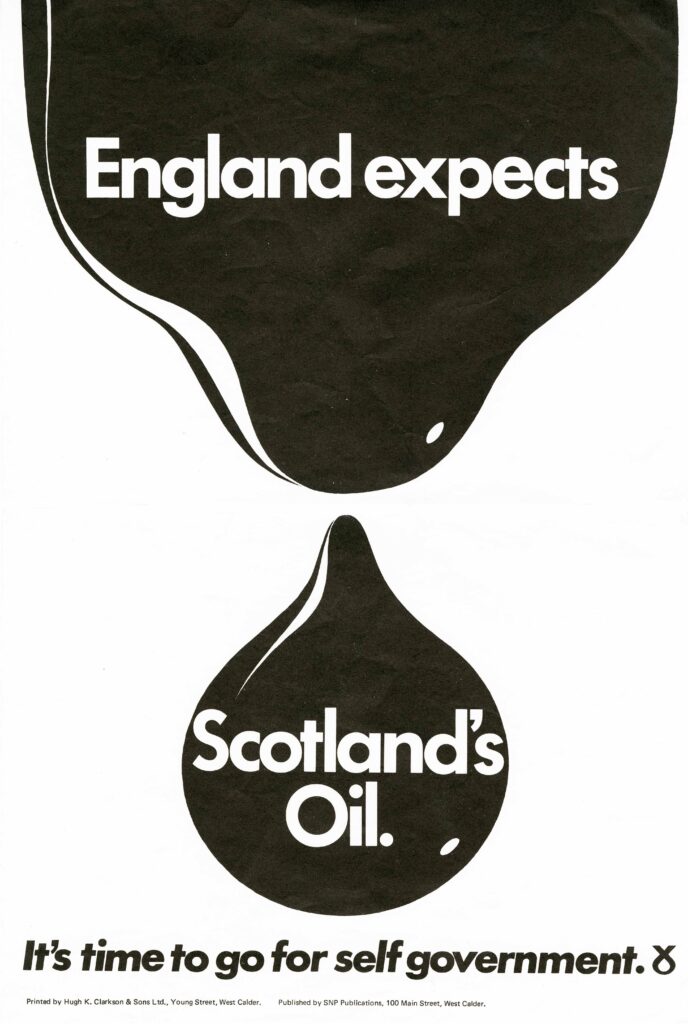

The SNP came to prominence as a major political force as North Sea oil’s stock rose.

Increasing SNP support encouraged Labour to offer a referendum on devolution in 1979. It failed.

Opposing both devolution and public control, the incoming Conservative Government won through.

Oil Arrives On-shore

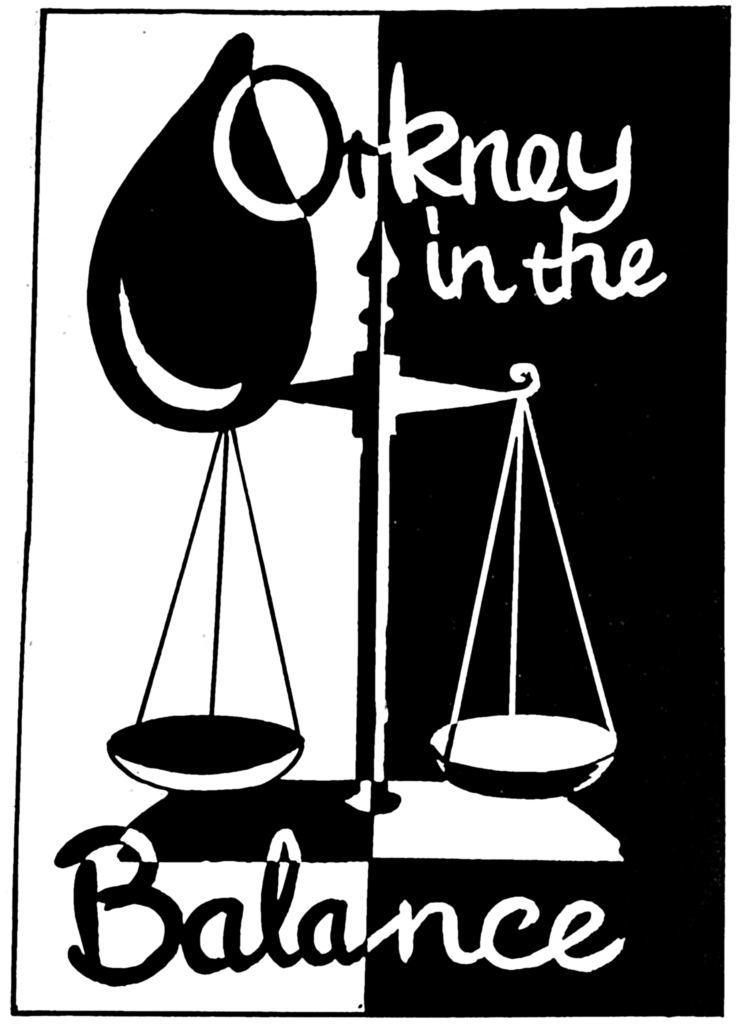

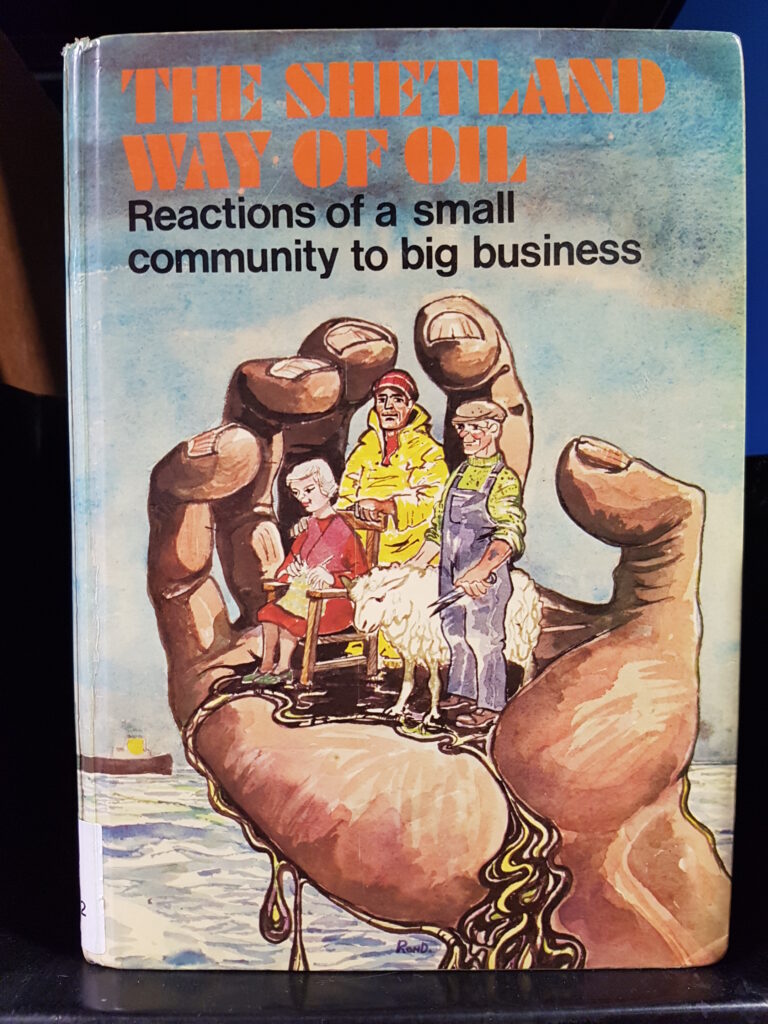

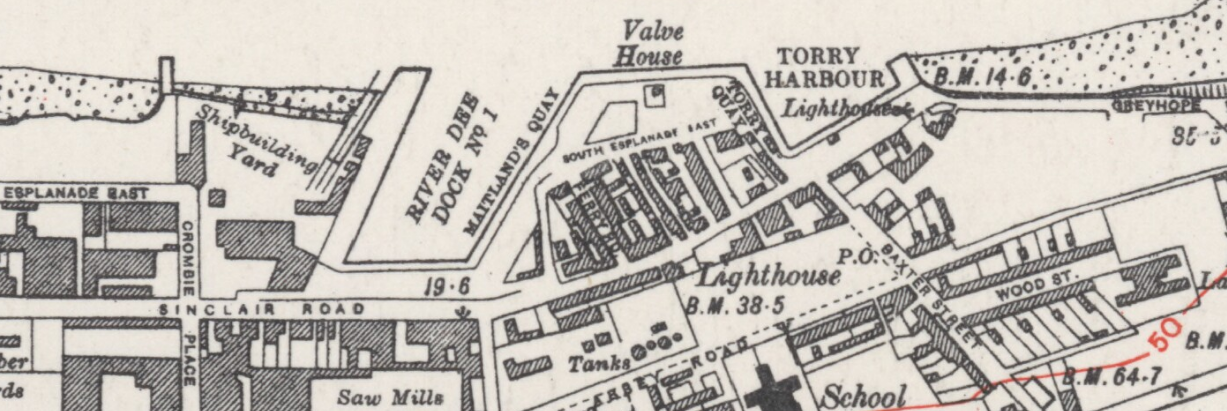

As more and more North Sea oil fields came into production local authorities competed to provide them with on-shore facilities, most notably in Shetland, Orkney and Aberdeenshire.

“The Torry people were helpless against the giant oil companies. Gradually the houses were vacated and as each family moved out, for the most part unwillingly, the windows were boarded up, the door securely padlocked. House after house was emptied until Old Torry resembled a ghost city.”

Mrs Elizabeth Finlayson, resident of demolished Aberdeen neighbourhood (1)

Fisherman in Shetland expressed serious concerns about the risks posed by oil pipelines.

Environmental group Friends of the Earth Orkney produced a pamphlet expressing concerns about oil development in Scapa Flow.

Well organised opposition of Fife residents held up construction of the Mossmorran gas plants by over a decade. (*)

Oil Culture

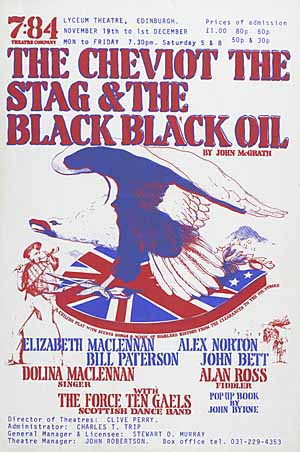

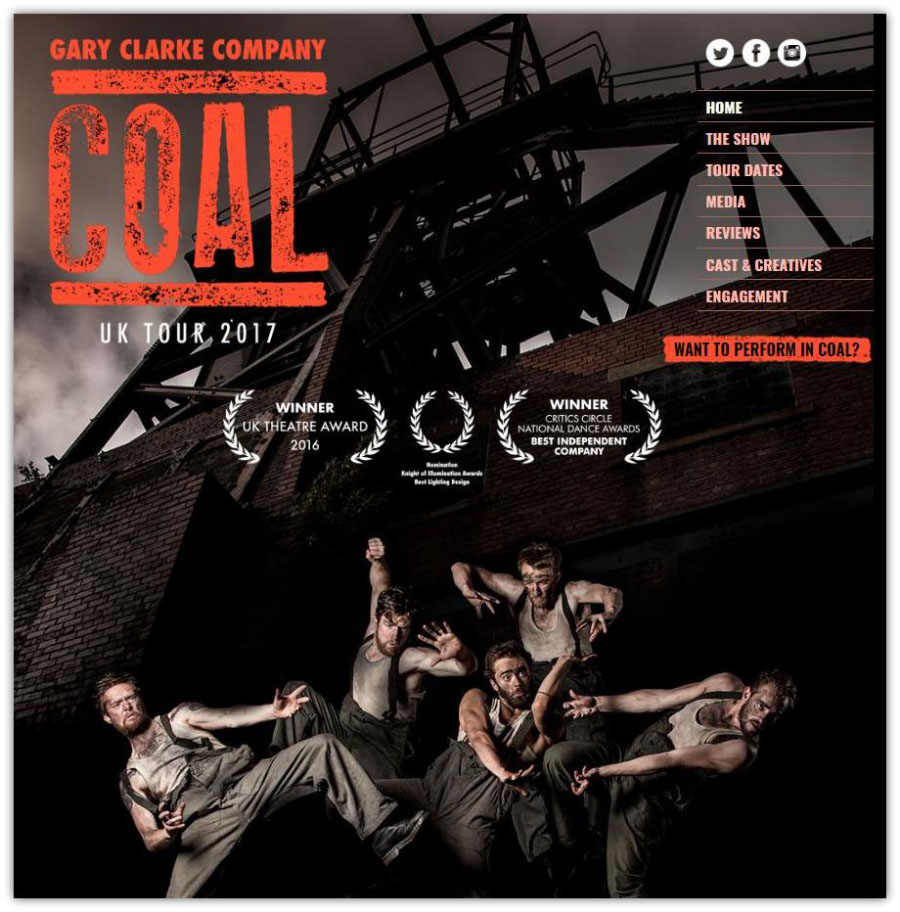

There is a rich seam of cultural reactions to Scotland’s coal and oil, including theatre, dance and film-making.

“Leave your fishing, and leave your soil,

‘Texas Jim’ from The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black Black Oil by John McGrath

Come work for me, I want your oil.

Screw your landscape, screw your bays

I’ll screw you in a hundred ways”

The play ‘the Cheviot, the Stag and the Black Black Oil’, 1973, is a folk play on three waves of exploitation of Scotland.

1983 movie Local Hero depicts the arrival of oil to small town Scotland.

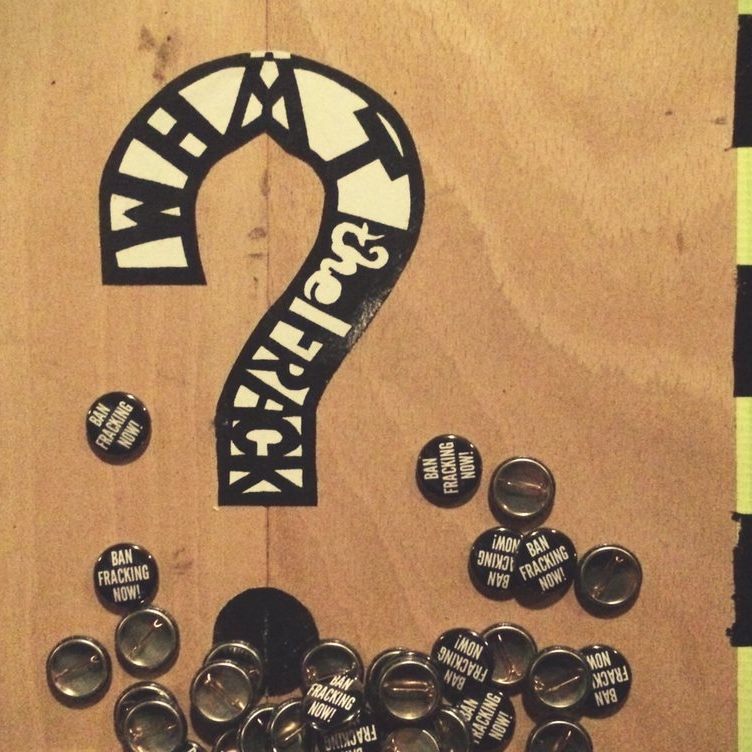

In 2017 queer performance artist ‘Activising for Change’ toured Scotland with ‘What the Frack’.

Ballet ‘Coal’ toured Scotland in 2017 and included striking families in the cast.

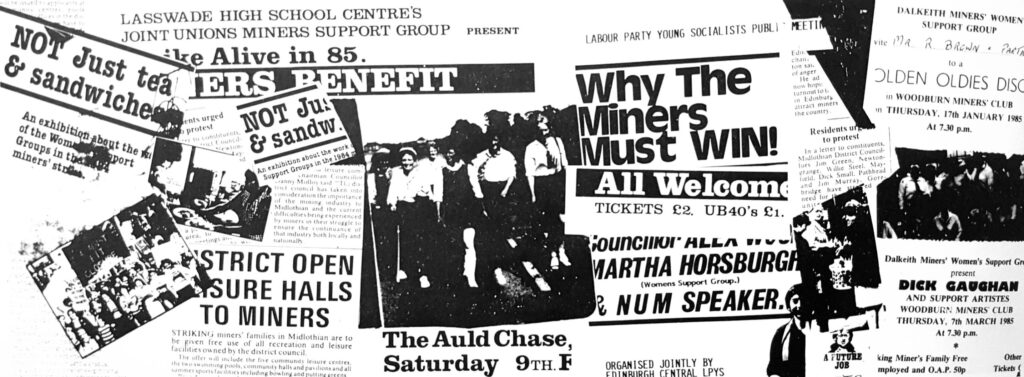

1984-5 Miners’ Strike

Between 1981 and 1984 a quarter of Scotland’s coal miners lost their jobs. Seeking to halt the demise of the industry, the National Union of Mineworkers went on strike.

Striking miners were supported by women’s groups, lesbian and gay groups, Labour local authorities and even school children.

“Pre-strike you’d see these marches like Greenham Common or CND, and you might agree with them but you wouldn’t walk through the streets with banners. But now I’ve done it a hundred times. It’s not until you do a thing that you realise you can do anything.“

Lothian Women’s Support Group member (2)

“Without your help; your support, this strike centre would have crumbled. You came along at just the right time and kept us going. We thank you for that.”

Jim, miner at Whitecraig, speaks to Lothian Lesbian and Gays Support the Miners (*)

“They were met with great hostility by pensioners, housewives and youngsters who poured abuse on them at every point along the road. The final straw for the lorry drivers came when well over 100 youngsters, between 12 and 14 years, instead of going into school, marched out on to the road down through the village to Lochore Miners’ Institute, singing and shouting and blocking the way of the worried lorry driver. They never re-appeared.”

Coal trucks meet resistance in Ballingry, Fife (3)

Following the end of the strike Scotland’s deep mining industry was privatised and shut down. The last deep coal mine closed in 2002.

Piper Alpha

167 people were killed when the Occidental-owned Piper Alpha platform caught fire, exploded, and melted into the North Sea.

“The death toll in the Piper Alpha oil platform disaster was feared last night to be 169. The biggest air-sea search in British maritime history was called off in fading light, almost exactly 24 hours after it began when spears of flame roared 700 feet into the air and melted the massive girders of the rig which had towered from the seabed.

“Hour after hour the frantic calls came in to Aberdeen. Grief, fear, shock, disbelief, a desperate searching for straws of hope – patient men and women at police headquarters shouldered the first terrible burden.”

Aberdeen Press & Journal, 8 July 1988

Survivors and their families organised as ‘OILC’, shutting down whole rigs and striking and protesting for better pay and working conditions.

Shell, Greenpeace and the Brent Spar

As North Sea fields began to age, oil companies were to face opposition regarding how they decommissioned spent infrastructure.

“International condemnation of Shell’s deep-sea dumping continued …the greatest opposition is in Germany, where calls for a boycott of Shell petrol have hit sales. Yesterday, one of its stations in Hamburg was firebombed. Another was shot at earlier this week.”

The Independent, 17 June 1995

“In the face of protests from environmentalists and several European governments, Royal Dutch Shell has abandoned its plan to sink an ageing oil platform in the North Atlantic, the oil company announced today. The British Government, which had backed Shell’s plans to sink the 65,000-ton, 450-foot-tall oil platform, reacted angrily.”

New York Times, 21 June 1995

After their victory at the Brent Spar, Greenpeace would go on to occupy Rockall in the North Atlantic, protesting oil extraction and declaring a new state called ‘Waveland’.

The End of Scotland’s Coal

The UK climate movement grew significantly from 2005. Direct action caused the cost of open-cast coal mining to spiral. Demand faltered as new coal power stations were rejected, including at Hunterston: a bellwether victory for NGOs and local communities.

By 2015 the coal industry was totally defeated.

“The proposed power station would have a devastating impact on our community, damaging our health, our livelihoods and destroying the local environment.”

Maggie Kelly, Communities Opposed to New Coal at Hunterston

[2009-08-06] Activists damaged a 6.5km conveyor belt which transports 200,000 coal each year from to Ravenstruther.

[2009-11] Activists sabotaged a specialist drilling rig and other machinery in Mainshill Wood. Cables were cut, controls damaged, levers busted, locks glued, windows broken, lights smashed. There were no injuries or arrests.

[2009-12-25] Mainshill camp celebrates Christmas and 6 months of occupation. Four mining machines are sabotaged at nearby Broken Cross mine as a “Christmas present” to Scottish Coal.

Indymedia

“Details have been released of the demolition of the landmark twin chimney stacks at the former Cockenzie Power Station site.

“The towers will be brought down by a controlled explosion at noon on Saturday.”

“Scotland’s last coal-fired power station, Longannet in Fife, is to close on 31 March 2016.”

BBC News (* / *)

Fossil Fuel Finance

As the climate movement grew, activists looked for new ways to stifle fossil fuel expansion.

In 2007 a new campaign targetted Europe’s largest bank: RBS. The global financial crisis soon led to greater public interest into financiers.

“The locks of the main entrances to at least six Edinburgh RBS branches were glued shut last night, and all of them had to have the locks replaced today.“

Indymedia, 15 October 2007

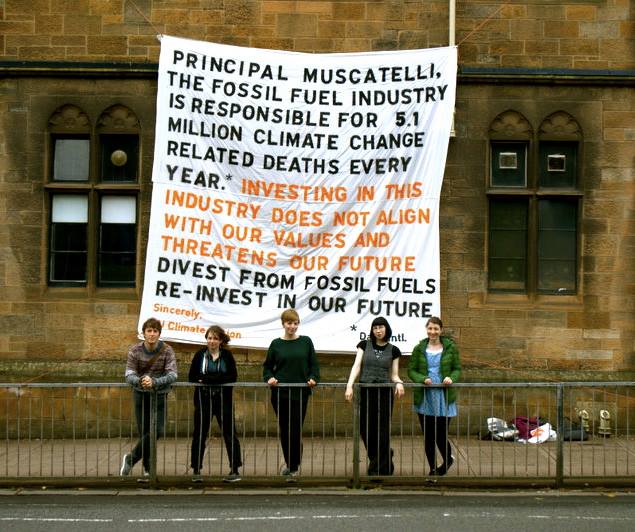

“We are delighted that the University of Glasgow has decided to take a committed stance against climate change and cut its financial ties with the fossil fuel industry. We hope that our university will serve as a role model for other universities.”

Sophie Baumert, Glasgow University Climate Action Society, 2014

Climate activists challenged financial and sponsorship ties between global oil brands and Scottish institutions.

EDINBURGH SCIENCE FESTIVAL TO BAN FOSSIL FUEL SPONSORSHIP DEALS

Edinburgh Evening News, 3 April 2019 (*)

The Movement to Ban Fracking

Facing dwindling reserves the oil and gas industry looked to new techniques to extract fuel. Fracking could enable gas to be exploited onshore in Scotland: but it would be near to people’s homes.

A vibrant network of local and national campaigns drew momentum from the 2014 independence referendum to stop fracking.

Anti-fracking groups protest outside the SNP Conference, Perth, 19 October 2013. Photo: FoES.

Anti-fracking protest at the Scottish Parliament. Photo: FoES.

Anti-fracking protest at Grangemouth, 2015. Photo: RL.

Protest against underground coal gasification, Portobello Beach, Edinburgh, 2016. Photo: FoES.

Friends of the Earth Scotland construct a ‘fracking rig’ outside SNP Conference, 19 October 2013. Photo: FoES.

“Thousands of letters were signed. MPs and MSPs were lobbied. Events and conferences were organised. Demonstrations were held at oil refineries. Communities were being very noisy, and their voices were being amplified by a newly attentive Scottish media.”

Lander/Young, European Green Journal, 2014 (*)

BLOCK ON FRACKING IN SCOTLAND ANNOUNCED BY MINISTER

28 January 2015, BBC (*)

“It speaks volumes about Scottish leadership on the world stage and sends a clear and negative message to any future investors in Scotland.”

INEOS Operations director Tom Pickering (*)

“This is a huge victory for the anti-fracking movement, particularly for communities on the frontline who have been fighting for a ban these last six years.”

Mary Church, Friends of the Earth Scotland (*)

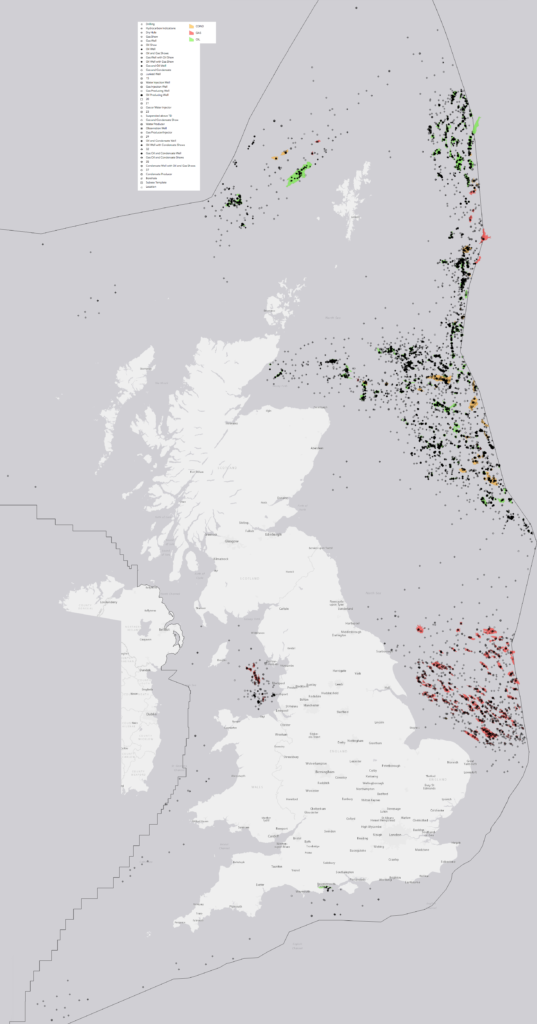

Scotland’s Oil Today

North sea oil and gas extraction peaked in the year 2000. But it is still a major industry with hundreds of active wells and tens of thousands of workers.

The SNP-run Scottish Government has failed to align their historic support for oil with their climate objectives.

“Tackling climate change is an overwhelming moral obligation that we owe to this and future generations.”

Nicola Sturgeon speech to the UN, 2017 (*)

“The Scottish Government will continue to support the oil and gas sector as strongly as we possibly can… our primary aim – and I want to underline and emphasis this – our primary aim is to maximise economic recovery of those reserves.”

Nicola Sturgeon speech to the oil and gas industry, 2017 (*)

Finding a Just Transition

Oil workers and oil communities demand good jobs and a future. Environmental activists seeking to protect communities affected by climate change are forming new alliances with trade unions to ensure that Scotland’s oil doesn’t go the way of the deep mining industry.

“Climate change arises principally from historically unequal economic and social structures, from practices and policies promoted by rich, industrialized countries, and from systems of production and consumption that sacrifice the needs of the many to the interests of a few. The affected peoples of the world bear little responsibility for the climate crisis yet suffer its worst effects and are deprived of the means to respond.”

The Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice

‘A proper industrial policy considering procurement, planning, licencing powers, public ownership and investment must be pursued if we are not to repeat the mistakes of the past.’

The Scottish Trades Union Congress seek a just, green economy, 2019

In 2019 the Scottish Government responded to these calls by creating a ‘Just Transition Commission‘ and by passing a new Climate Change Act.

Disobedience Returns

In 2018 Extinction Rebellion was launched in Scotland and the youth climate strikes began.

Hundreds of protests took place between 2018 and the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 seeking a just transition away from oil.

Activists and their allies are gearing up to oppose oil at the forthcoming United Nations climate talks in Glasgow, scheduled for November 2021. As climate change becomes more lethal support for a shift away from Scotland’s oil seems likely to grow.

The story of resistance to Scotland’s fossil fuels industry is still being written.

End bits

Zine

In 2019 this story was made into a zine to raise money for the Unity Centre, Glasgow.

You can download the zine to read online or print at home. Hard copies can also be obtained by contacting the author.

Further reading

If you want to learn more about the radical history of fossil fuels in Scotland and the UK, here’s some great books to read:

Carbon Democracy, Timothy Mitchell, publisher link.

Digging Deeper explores different histories of the 1984-5 miners strike, edited by Huw Beynon. Purchase link.

Lothian Women’s Support Group pamphlet is available at the City of Edinburgh Library.

Coal Action Scotland members produced a zine about their occupation. Read it online.

Referendum era debates on the future of Scotland’s energy industry. Read online here.

A radical tour of Grangemouth, by bike! Read online here.

Also check out these articles:

- Picture story, ‘The Miners’ Strike in Scotland, 1984-5′, Canmore. View online.

- ‘Going on the Offensive – A Picture of Scotland’s Anti-Fracking Movement.’ Ellen Young and Ric Lander, 2015. Read online.

- ‘Brent Spar, the Battle that Launched Modern Activism.’ Read online.

- ‘Royal Bank of Scotland: 10 years of climate campaigning.’ Ric Lander, 2018. Read online.

- ‘Sea Change: Climate Emergency, Jobs and Managing the Phase-Out of UK Oil and Gas Extraction.’ Friends of the Earth Scotland, 2019. Read online.

- ‘Stories of environmental injustice: Petrochemicals in Grangemouth.’ Open website.

- ‘After 160 years Central Scotland has had enough.’ Ric Lander, 2013. Read online.

- ‘I’ve always loathed royal occasions’, extract from the Tony Benn Tapes, 1993. Listen here.

- ‘A climate justice reading list.’ 350.org. Open webpage.

The author

Ric Lander is an environmental activist and campaigner at Friends of the Earth Scotland. In 2008 he graduated with an MSc in Environment & Development from the University of Edinburgh and has since been writing, tutoring and speaking on environmental justice issues. In recent years he helped found Climate Camp Scotland and the Scottish Community & Activist Legal Project.

Sources

Most quotes have a link to the source in the citation that immediately follows.

Where there is a number instead, quotes are derived from the following books:

- ‘The Klondykers: the Oil Men Ashore.’ Bill Mackie, Birlinn, 2006

- ‘Women Living the Strike’, Lothian Women’s Support Group

- ‘The Mineworkers’, Robert Duncan, 2005

Some newspaper quotes refer to archival articles which are not available online.

In addition, the following sources provided invaluable background:

- ‘Collieries, Communities and the Miners’ Strike in Scotland, 1984–85.’ Jim Phillips. Manchester University Press, 2012

- ‘The Oilmen: the North Sea Tigers.’ Bill Mackie, Birlinn, 2004

- ‘Shetland Way of Oil: How a Small Community Reacts to Big Business.’ Thuleprint, 1976

- ‘Crude Britannia: the Story of North Sea Oil’, BBC Four.

Image credits

Images credited to ‘RL’ are licensed for non-commercial re-use (see here) by Ric Lander.

Images credited to ‘FoES’ are copyright Friends of the Earth Scotland, used with permission.

Where credits are missing it has not been possible to find the original author, please contact me to remedy this!

Copyright

The last major update was made in July 2020.

Unless otherwise stated, the contents is available for re-use and re-sharing. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.